-

Mike Collins (CAPCOM)

Mike Collins (CAPCOM)

-

We have 1 minute to LOS, Frank. You can terminate stirring up your cryos any time, and we agree with all your flight plan changes. Have a beautiful backside, and we will see you next time out.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Roger, Apollo 8. Couple of notes for you: on the P52 you are coming up to on this REV, we've looked at your state vectors and all your information. The platform looks good, and it appears that it is your option if you would like to by-pass this P52, your platform will still be good at the following TEI pass. And we would like to have your PRD reading, and I guess we are behind the sleep summary. Over.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Copy, 144. And we have an update ready to go into your computer for the state vector if you want to go to P00 and ACCEPT.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Okay, Apollo 8. We have completed with the computer. You can use the VERB 47 to transfer, and I have the TEI 9 PAD.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

That's Ken isn't it? Just a minute, and I'll take care of it.

Expand selection up Contract selection down Close -

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

Okay. This PAD is a TEI 9, SPS/G&N: 45597, minus 040, plus 157 087:19:18.20, plus 34188, minus 01353, plus 00780 180 008 001, November Alfa, plus 00187 34223 313 34021 42 0898 253 033, down 131, left 28, plus 0758, minus 16500 12987 36277 146:48:16; primary star Sirius, secondary Rigel, 129 155 010; four quads, 15 second, ullage, horizons on 1.2-degree window line at T minus 3; use high speed procedure with minus Mike Alfa. After looking at the burn information from your previous SPS burns, it appears that the engine performance should give us a 3-second burn time, longer than what you have on the PAD. The PAD number should correspond with what you get out of the computer. So we have not factored this into the past data; however, you can anticipate the engine for a normal DELTA-V to give you a 3 second—3.7-second burn in excess of the computed times. Over.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

TEI 9, SPS/G&N: 45597, minus 040, plus 157 087:19:18.20, plus 34188, minus 01353, plus 00780 180 008 001, NA, plus 00187 34223 313 34021 42 0898 253 033, down 131, left 28, plus 0758, minus 16500 12987, plus—or 36277 146:48:16; and that's Sirius and Rigel 129 155 010, four jet, 15 seconds, 1.2 degrees on the window at T minus 3, high speed minus MA, engine 3.7 seconds longer than given.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

That's affirmative, Apollo 8. And when you get around to it, if you would like for us to dump your tape, we can do that when you get on the high gain.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Apollo 8, we'll have one for you the next time around, and we'll update it if necessary on the following REV.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

Do you have any idea why quad B seems so much lower in quantity than the other three quads?

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Okay. It looks to us like, although we're reading out the same thing you are on the quad quantity, using the computer program and all of the correction factors that are in there, it looks like all four of your quads are very close. In pounds, it looks like you have, for example, 193 pounds in quad A and 189 in B, 200 in C, and 190 in Delta. And the difference that you read on the gage is attributed to the fact that you don't have all of the correction factors in there. This ground calculation has an accuracy of about plus or minus 6 percent, and the best you can do on board, even using your chart, is plus or minus 10 percent. Over.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Okay. We've just finished looking at all your systems and all the trajectory information, and you have a GO for another REV.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

If you're looking for things to do up there, Frank, you might hit that BIOMED switch over to the left position.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

Hey, Ken; how did you pull duty on Christmas Eve? It happens to bachelors every time, doesn't it?

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Okay. Frank, it's looking like it's coming right down the pike. It's doing just what it is supposed to, and apparently, all our computer programs have got the right numbers in them because they're predicting where you're going.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Roger. They're detectable, but they're not changing, things enough to be anything more than—of interest.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

Fine. Hope they are as good with the corridor as they were with the LOI. That was beautiful.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Okay. We're about—inside 10 minutes till LOS. We'll be picking you up again at 85:40, and we'll have all of the TV types' information standing by. In the event that the situation develops again, for pointing accuracies, if I see anything that looks like a terminator or anything of that nature, I'm going to call the dark side of it 12 o'clock, and use that as a reference system, and we'll try that. If that doesn't dope out any problems with camera pointing, why I may try—call for a plus pitch, and then I'll just correct what I see to account for it.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

Roger. We're not going to use the telephoto lens. I don't believe we'll be able to get a picture of the earth. It's going to have to be the terminator, the lunar surface. I'm looking at the earth right now; and we won't see it again during that period.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Okay. Real fine then. And next time around, why, we'll take an extra special look at all of the parameters; we'll have our TEI PAD for you. And we'll use the last REV for a real good hack on all systems. I'll give you a rundown by system of all things we see and where they stand.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

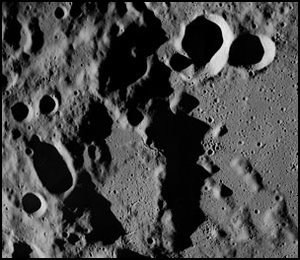

Houston, you're seeing a view of the earth taken below the lunar horizon. We're going to follow a track until the terminator, where we will turn the spacecraft and give you a view of the long shadowed terrain at the terminator, which should come in quite well in the TV.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

We don't know whether you can see it from the TV screen, but the moon is nothing but a milky white—completely void. We're changing the cameras to the other window now.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

This is Apollo 8, coming to you live from the moon. We've had to switch the TV cameras now. We showed you first a view of earth as we've been watching it for the past 16 hours. Now we're switching so that we can show you the moon that we've been flying over at 60 miles altitude for the last 16 hours. Bill Anders, Jim Lovell, and myself have spent the day before Christmas up here doing experiments, taking pictures, and firing our spacecraft engines to maneuver around. What we will do now is follow the trail that we've been following all day and take you on through to a lunar sunset. The moon is a different thing to each one of us. I think that each one of us—each one carries his own impression of what he's seen today. I know my own impression is that it's a vast, lonely, forbidding-type existence, or expanse of nothing, that looks rather like clouds and clouds of pumice stone, and it certainly would not appear to be a very inviting place to live or work. Jim, what have you thought most about?

-

Jim Lovell (CMP)

Jim Lovell (CMP)

-

Well, Frank, my thoughts are very similar. The vast loneliness up here of the moon is awe inspiring, and it makes you realize just what you have back there on earth. The earth from here is a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

I think the thing that impressed me the most was the lunar sunrises and sunsets. These in particular bring out the stark nature of the terrain, and the long shadows really bring out the relief that is here and hard to see at this very bright surface that we're going over right now.

-

Frank Borman (CDR)

Frank Borman (CDR)

-

You're describe—that's not color, Bill. Describe some of the physical features of what you're showing the people.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

We're now coming on to Smyth's Sea, a small mare region covered with a dark, level material. There is a fresh, bright, impact crater on the edge towards us and a mountain range on the other side. These mountains are the Pyrenees.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Apollo 8, we're reading you loud and clear, but no picture. We have no modulation.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

What you're seeing has been cross—Smyth's Sea are the craters Castner and Gilbert, and what we've noticed especially, that you cannot see from the earth, are the small bright impact craters that dominate the lunar surface.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

The horizon here is very, very stark. The sky is pitch black, and the earth—or the moon, rather, excuse me—is quite light; and the contrast between the sky and the moon is a vivid, dark line. Coming into the view of the camera now are some interesting old double ring craters, some interesting features that are quite common in the mare region and have been filled by some material the same consistency of the maria and the same color. Here are three or four of these interesting features. Further on the horizon you see the … The mountains coming up now are heavily impacted with numerous craters whose central peaks you can see in many of the larger ones.

-

Jim Lovell (CMP)

Jim Lovell (CMP)

-

Actually, I think the best way to describe this area is a vastness of black and white, absolutely no color.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

The sky up here is also rather forbidding, foreboding expanse of blackness, with no stars visible when we're flying over the moon in daylight.

Expand selection down Contract selection up -

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

You can see by the numerous craters that this planet has been bombarded through the eons with numerous small asteroids and meteoroids pockmarking the surface every square inch.

-

Jim Lovell (CMP)

Jim Lovell (CMP)

-

And one of the amazing features of the surface is the roundness that most of the craters—seems that most of them have a round mound type of appearance instead of sharp, jagged rocks.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

Only the newest feature is of any sharp definition to them, and eventually they get eroded down by the constant bombardment of small meteorites.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

The very bright features you see are the new impact craters, and the longer a crater has been on the surface of the moon, why, the more mottled and subdued it becomes. Some of the —

-

Jim Lovell (CMP)

Jim Lovell (CMP)

-

Houston, we're passing over an area that's just east of the Smyth's Sea now, in checking our charts. Smyth's Sea is coming up in a few minutes.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

We are now coming up towards the terminator, and I hope soon that we'll be able to show you the varying contrast of white as we go into the darkness. Houston, we're in P00, and you have the computer.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

We're now approaching a series of small impact craters. There is a dark area between us and them which could possibly be an old lava flow.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

You can see the large mountains on the horizon now ahead of the spacecraft to the north of our track.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

The intensity of the sun's reflection in this area makes it difficult for us to distinguish the features we see on the surface, and I suppose it's even harder on the television, but as we approach the terminator and the shadows become longer, you'll see a marked change.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

There is a very dark crater in the filling material in this valley in front of us now. It is rather unusual in that it is sharply defined, yet it's dark all over its interior walls, whereas most new-looking craters are of very bright interior.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

Small impact crater in front of us now in the little mare well defined, quite new, and another one approaching. The spacecraft is facing North. From our track, we are going sideways to our left.

-

Bill Anders (LMP)

Bill Anders (LMP)

-

We believe the crater, the large dark crater between the spacecraft and the Sea of Crises is Condorcet Crater. The Sea of Crises is amazingly smooth as far as the horizon and past this rather rough mountainous region in front of the spacecraft.

-

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

Ken Mattingly (CAPCOM)

-

Apollo 8, we are through with the computer. You can go back to BLOCK, and it looks like we are getting a lot of reflection off your window now.

Spoken on Dec. 25, 1968, 12:51 a.m. UTC (55 years, 10 months ago). Link to this transcript range is: Tweet